How Should We Conduct Investigations

Scott Mitchell

Scott is the Founder of OCEG, the global nonprofit that created GRC and Principled Performance.

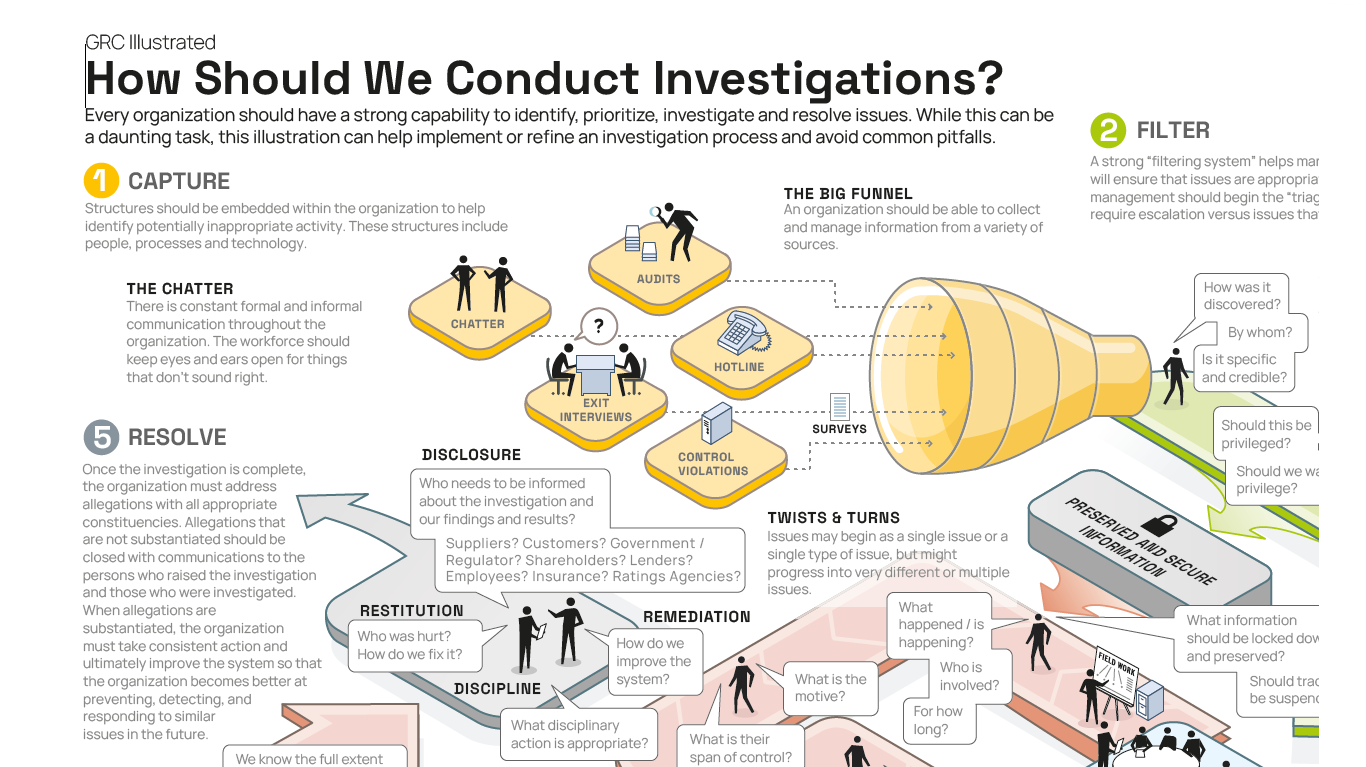

Every organization should have a strong capability to identify, prioritize, investigate and resolve issues. While this can be a daunting task, this illustration can help implement or refine an investigation process and avoid common pitfalls.

The first ever investigation was a difficult one, even when there was only two potential perpetrators, a single location, a tree and an omniscient investigator.

Things have become much more complex and, in most cases, we do not have the benefit of an omniscient investigator. As such, most organizations should define an approach to internal investigations to improve effectiveness while reducing costs and complexity.

Establishing a clearly defined process helps management quickly respond to allegations of wrongdoing and actual violations in a rational, rather than ad hoc or crisis manner. In other disciplines such as software development, we know that a reactionary response to “bugs” can cost five times more versus a planned response.

A recent conversation with a chief compliance officer at a large industrial manufacturer suggests that this rule is applicable to internal control and compliance.

He noted, “After we organized our approach to investigations, our costs dropped dramatically – unfortunately, it wasn’t for lack of investigations. As investigations volume went up, our annual costs actually went down 15%.”

Multinational organizations will find even more efficiencies as cross-border investigations tend to be even more ad hoc and fragmented. The good news is that it takes relatively little time to define a robust internal investigations process.

The same executive above noted, “It took about 200 hours of internal staff time and about 100 hours of external help to nail down our process. In the end, we saved at least that much time in our first investigation.”

While a specific internal investigations process may comprise five or fifty steps, the following key phases should be present and clearly defined.

Capture

This is the precursor to an internal investigation. It is helpful to have a “big funnel” to channel information to a team charged with filtering and vetting this information. The funnel should comprise a number of “push” and “pull” structures.

Push structures include:

- Hotline/Helpline is one of the obvious mechanisms to allow the workforce and other stakeholders to report (confidentially or anonymously) allegations of misconduct. The helpline can also provide input as high volume of questions about a particular subject may indicate confusion about expected conduct and, in turn, increase the risk of actual misconduct.

- Employee performance assessments provide an opportunity for management to encourage employees to openly discuss any issues that they observe. Of course, it is unlikely that employees will open up about issues related to the manager asking the questions, but this can lend to the discussion about other issues.

- Control violations that are automatically triggered based on threshold conditions can raise “yellow flags” that misconduct may have occurred. Management will most likely have to use human judgment to determine if these violations are actually issue of interest.

Pull structures include:

- Confidential employee surveys provide a literal “ask and answer” mechanism to get responses from the workforce about specific issues.

- Exit interviews provide an opportunity to find out what is really happening in a department. People tend to be extremely honest as they are walking out the door.

- Surveillance including video, audio and physical (e.g., RFID tags) monitoring many be necessary for high risk locations and/or transactions.

- Audits and assessments include all of the proactive evaluation of controls and other information on a periodic and ongoing basis.

In addition, management should pay attention to all of the “chatter” in the organization – the formal and informal conversations that take place verbally and via email. Sophisticated email filtering technologies can look for interesting phrases such as, “Do we really want to do this?” or “I don’t feel comfortable putting that in writing.” All of these techniques need to be balanced with the potential of creating a tattletale, gadfly or Big Brother culture which will result in decreased workforce productivity.

Filter

Once information about potential violations is captured, it must be filtered so that the investigations team can focus on what matters most. The goal of filtering is to discard allegations that are not specific and credible; and appropriately act on those that are. It is critical that the individuals charged with this determination are both competent and independent. Some issues may require a level of technical analysis to make this determination. It is wise to have these individuals available in the early stages of filtering. Key questions to answer include:

- How was the issue discovered?

- By whom?

- Is it specific and credible?

If there is not sufficient information captured about a violation, it will be extremely difficult to determine if it is specific and credible. As such, while it is not absolutely necessary, it is helpful if reporters and sources of allegations are able to be contacted for follow-up and clarification. It is also important to discern whether the source has a motive to lodge a frivolous allegation.

Even at this early stage, the team should attempt to determine if the issue should be handled under privilege. Every step not taken under privilege can introduce more risk to the organization as untrained individuals may capture facts and testimony that have no chance of being privileged later on. On the other hand, every issue cannot and should not be vetted and investigated under privilege. For some issues, privilege is simply overkill and, according to one enforcement official, “The obsessive compulsive assertion of privilege is one of the things I look for when I try to determine if an organization is sincere about its need to maintain privilege. It is statistically impossible that everything should require privilege and, thus, I treat organizations that have an ‘everything is privileged’ culture with increased skepticism.”

Another important consideration here is that, even as early as the filter stage, the clock begins to tick. Simply read the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for Organizations, the McNulty Memo and the often overlooked 21(a) Report of Investigation of Seaboard to understand the importance of a spry internal response to serious allegations. A quick response and, if appropriate, disclosure to the government is the only way that the organization can be spared the damage caused by the blunt tools available to the government should they become involved in a matter.

Plan & Assign

Based on the alleged and/or confirmed facts, circumstances, nature and seriousness of the issue, the team should assign the issue to the appropriate investigations “work stream” or “tier” as some organizations call it. Using a tiered system ensures that issues of similar nature and seriousness are handled in a similar way. In addition, it allows the organization to allocate scarce capital – both human and financial capital – to investigations.

When assigning issues to a tier and team, an organization should consider:

- Nature and seriousness of the issue;

- Skills and experience required to obtain and analyze facts (legal, accounting, technology, forensic and other industry expertise);

- Independence from the issue at hand (e.g., to not assign a financial investigation to a team that includes staff from the office of the CFO); and

- Availability of resources.

I know this last item sounds obvious, but a timely follow-up and investigation is important especially for serious issues that may involve the government.

While an organization may choose to have fewer or additional tier, at least four will be helpful:

Tier 1: Critical Issues. This tier is reserved for “sink the company” issues that are material to either the financial or reputational health of the organization – or issues that involve senior executives. These investigations are directed by the board and involve significant outside assistance to ensure objectivity. Privilege is a must at this level. For public companies, the involvement of the external auditor may be required or at least advised.

Tier 2: Significant Issues. These issues are serious and material to the organization but do not involve allegations of wrongdoing by senior management. As such, senior management directs these investigations with special care and under privilege.

Tier 3: Serious Issues. Most organizations have issues that they, to a certain degree, expect and prepare for, such as a significant theft. Systems have been designed and special investigative staffs have been trained to address these issues.

Tier 4: Operational Issues. These issues, often HR related, warrant the attention of management, but may not require privilege or professional investigators. They are often delegated to management, but could escalate at any phase. Some of these issues are resolved without the need for investigative resources.

With each of these tiers it is important to define who does what. Critical roles include:

- Leadership for day-to-day management of the investigation;

- An individual charged with communication about the status of the investigation with stakeholders such as the source of the allegation, the media, and most importantly the government; and

- Staff and outside consultants who will obtain and analyze the facts.

As a final note, it is wise to limit knowledge that a particular investigation is being conducted. The risk of evidence tampering and destruction increases when it is broadly known that an issue is under investigation.

Investigate

At this point, the right people are in place to conduct the investigation using predefined protocols given the tier to which it was assigned. Regardless of which tier, some common questions must be answered:

- What happened / is happening?

- Who is involved? How many are involved? How senior are they?

- For how long has this been going on?

- What was the motive?

- What other activities are under this person’s purview? What is their span of control?

- Has anything similar happened with this person in the past? Anything at all?

- Why did they do it?

- Was it carelessness? Was it a mistake in judgment?

- Was it a lack of training or clarity in policy, procedures or controls?

- Was it pernicious?

- Were there “perverse incentives” in place that led this person to commit these acts?

- What else could be affected?

- How much harm was caused? Who was hurt?

To answer these questions, the investigations team should follow predefined protocols for gathering evidence including interviews, surveillance and other methods. Try to conduct all interviews in person so that nonverbal queues can be analyzed. Review all relevant documentation prior to the interview so that you can corroborate what you already believe to be factual as well as to direct questions to fill in gaps. At the beginning of the interview it is important to provide appropriate warnings:

- Upjohn Warning. An employee should be told at the beginning of every interview that the interviewer is representing the company’s interests and not theirs, and that the information being obtained is to provide legal advice to the company. The employee should be told that the interview is covered by attorney-client privilege and that the company, not the employee, may decide to either keep the information confidential and privileged or to waive this privilege in the future. Although there is no ethical obligation to legally advise the employee to obtain an attorney, it is an increasingly common practice to make this suggestion at the beginning of the interview. While, Upjohn is specific to interviews directed by counsel, this protocol is helpful for non-legal interviews as well. In some ways, it is common courtesy to let employees know that the intention behind the questions is to serve the company and not to serve them.

- Zar Warning. To the extent that internal investigations are part of, or contemplated to be part of, a government investigation or government disclosure, employees should be informed that information obtained in the interview may be turned over or filed with the government. This is important because any false statements provided as part of an interview that is ultimately filed or disclosed to the government could result in obstruction charges. Some argue that this warning may actually cause more obstruction, or at least less cooperation as discussion about potential felonies can quickly chill a conversation.

As the investigation progresses, it will often take twists and turns. An issue may transform into a different or even multiple issues. At one global technology firm, the chief internal investigator found that, “Last year, two allegations about financial misconduct ended up being little more than lovers’ quarrels. While these are still important issues, they were nothing like what was initially reported.” The opposite can happen as well. Sometimes more minor allegations about a single issue may transform into more pervasive misconduct. At any point during the investigation the team may consider changing the tier and thus approach to the investigation. Always think about whether it needs to be escalated and self-reported to regulators.

It is important to not make premature predictions until the investigation has concluded as they provide nothing more than interesting (or more likely uninteresting) gossip. Reserve and report final judgment once the investigation has concluded.

Know When to Stop

The art of the investigation is knowing when to stop. Knowing when the issue has been thoroughly investigated. Knowing when there are no credible loose ends. Be aware that outside consultants and counsel, through no perniciousness of their own, have an incentive to pursue every last possibility. However, at some point you have to stop digging. Instead of asking “Is it possible?” begin asking “is it probable?”

Resolve

Once the investigation is complete, the organization must address allegations with all appropriate constituencies. Allegations that are not substantiated should be closed with communications to the individuals who raised the issue and to those who were investigated. When allegations are substantiated, the organization must take consistent action and ultimately resolve the issue including:

- Restitution to make harmed parties whole;

- Discipline to appropriately warn, demote or even terminate involved parties;

- Disclosure as appropriate to the government, customers, suppliers, regulators, shareholders, lenders, employees, insurance and ratings agencies as appropriate; and

- Remediation to fix any weakness in the system or improve the system to better prevent, detect and respond to similar issues in the future.

In fact, even when issues are not substantiated, there may be opportunities to improve the system.

Data, Documentation & Discovery

As part of the investigations process, an organization needs a protocol for issuing a “preservation notice” that instructs the workforce to suspend any routine data destruction activities and to proactively preserve information related to the investigation. As important are the actual procedures that ensure that the preservation notice can be affected. Make sure that all back-up and data protection processes will not overwrite critical information once a preservation notice is sent out. This is especially important for automated procedures.

New changes to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) note the importance of “electronically stored information” and how this information should be handled and shared during an investigation. To the extent that an internal investigation becomes relevant to the government or some third party, the company must be prepared to provide details about where data is stored and how it is created, managed, archived, destroyed, etc. Keep a close watch on this evolving area.

Global Considerations

If all of this is not daunting enough, consider the increased complexity presented by cross-border investigations. Key issues include:

- Data Protection. Rules governing how personal information must be handled are different all around the world. For example, the European Union’s Directive on Data Protection restricts the transfer of personal data to non-EU nations that do not meet the European “adequacy” test for privacy protection. Namely, the United States. As such, any information gathered in the EU before or during an investigation may or may not be allowed to be transmitted to a U.S. location for analysis or follow-up. At least two of the major hotline companies have established protocols for overcoming this obstacle.

- Evidence Collection Protocols and Witness Rights. In some jurisdictions, management and internal investigators are restricted from collecting information stored on company property once it is in the hands of an employee. One internal investigator noted, “We are not allowed to pull data from our laptops in France, even though the company owns the laptop and we have technical access to the drives.”

- Cultural Differences. The most obvious and significant challenge is less technical and more cultural. Local customs may lead employees and witness to share more, or typically less information with investigators. Deep cultural roots of loyalty to one’s boss or the company may lead individuals to be less cooperative when questioned. In some cultures, the notion of “telling on neighbors” may reduce the effectiveness of hotlines. In a recent discussion, the chief compliance and ethics officer of the largest Korean steel company presented an approach whereby individuals were awarded $50,000 for reporting issues that were later substantiated. This, he said, was paramount to breaking through the cultural preference for deference to supervisors and senior executives.

One way to deal with these global considerations is to identify, in advance, a local firm to assist with future investigations. Having a memorandum of understanding in place rarely involves any financial commitment but does require some time to identify and vet local firms.

Featured in: Investigations , Assurance / Audit